Practical Life Curriculum

Building Independence and Attention

“We must help them to learn how to . . . dress and undress, to wash themselves, to express their needs in a way that is clearly understood, and to attempt to satisfy their desires through their own efforts. All this is part of an education for independence.”

by Dr. Maria MontessoriBuilding Independence

The Practical Life part of our primary classrooms is aimed explicitly at helping children become

independent, so that they neither need nor are constantly soliciting the help of adults. As

Dr. Montessori put it:

The Montessori materials are designed and our teachers are trained to help the child learn how to break

down the required actions, to perform them step-by-step, and to do them repeatedly. As he systematically

acquires skills for self-care (dressing, tying shoes, washing hands) and care of his environment (washing tables,

preparing food, watering plants), the child gains independence from adult help. At an age during which he might

otherwise throw tantrums over wanting to “do it all by myself,” but not be able to accomplish the desired task,

he learns to do it.

“The environment is a place where the children are to be increasingly active, the teacher increasingly passive. It is a place where the child more and more directs his own life; and in doing so, becomes conscious of his own powers. . . . [The resulting love] for the environment does not exclude his love for the adult; it excludes dependence. It is true that one adult—the directress—is in a sense a part of his environment, but the function of both the directress and environment is to assist the child to reach perfection through his own efforts.”

by M. Standing, Dr. Montessori’s biographerTeaching Approach

One to One Teaching with individual presentation

Independent Work to Achieve Mastery

In our Montessori primary classrooms, learning happens in two main steps:

1. Introducing the material – “presentation”

Through careful observation of her students, the teacher identifies the most suitable material to introduce to each child and the best time at which to introduce it. She chooses an activity that is at the right level of difficulty for a particular child, something that presents a challenge but is within the range of his abilities. She then invites the child to join her in a presentation. (He is free to decline.) The presentation itself is focused on introducing a material, as simply and with few words as possible.

Inside View

For example, to introduce the “buttoning frame”, the teacher will ask a student to choose a table, get the dressing frame and place it on the table. She will sit on a small chair, next to the child, and demonstrate how to button the frame. She will open up the buttons, and fold the cloth apart. Then, using slow, accentuated movements, she will go through the process of buttoning, step-by-step – aligning the edges of the cloth so the buttons are aligned with the holes; carefully inserting one side of the button into the hole from below the cloth, pulling it through, and straightening it out neatly on top of the cloth. Throughout the presentation, the emphasis is on action, not words – to enable the child to watch and learn, and not be distracted by superfluous language. After the presentation, the teacher invites the student to try the activity, and provides guidance as needed to help him accomplish the task.

2. Individual repetition of the activity to achieve mastery.

Dr. Montessori observed that if an activity was introduced to the child in such a manner, and the activity was developmentally appropriate – that is, if it helped the child develop some skill or mental power his past experiences had prepared him to learn – the child would repeat the activity over and over again, until he achieved proficiency. The truth of this identification is evident in our classrooms, where we see that when each child has access to all the materials, and can choose freely what “works” he wants to engage with throughout the extended work periods, he does indeed repeat the exercises that he’s ready to learn. We see also that once he acquires proficiency, if the observing teacher presents him with the next demonstration, he naturally embraces the new challenge.

Inside View

The materials we use are largely “self-correcting”: they are designed

so that the child can recognize on his own, without the teacher, whether he has completed the activity

correctly. This is particularly true of the Practical Life activities: when he carries a pitcher full

of water, and does not coordinate his movements, the water will spill; when he pours rice from one container

into another, any grains that land on the table provide feedback to pour more carefully next time; when he

drops a real glass and it breaks, he learns about the need to better balance the little tray.

By locating the feedback within the materials, we free the child to learn directly from reality – to

recognize that the reason to do the work is not to get the approval of adults or other children,

but to succeed at a real task, objectively, through his independent effort, and by his own thinking

and judgment.

Key Activities

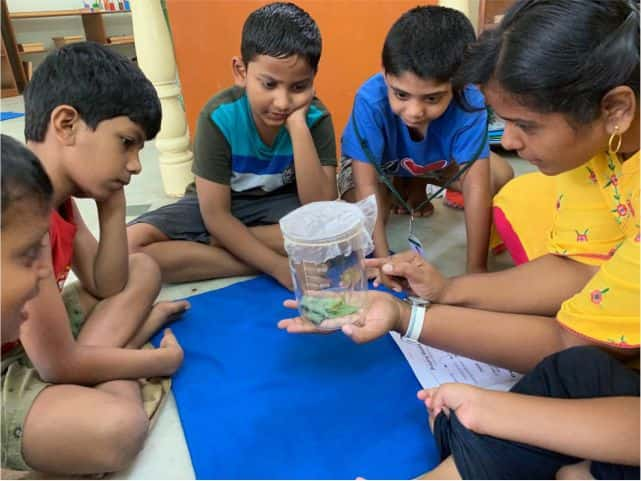

Real, Everyday Meaningful Activities – Made Possible with Thoughtfully Selected Materials

Learning by living in a real world

The Practical Life exercises use familiar objects the child also encounters at home – little

pitchers to practice pouring; tongs with which to transfer small objects from one container to another;

dishes to wash, brushes, squirt bottles; shoes to polish; food to clean, peel and cut; flowers to arrange

and plants to water. The activities are arranged on small trays and we use real, child-sized, high-quality

items, made out of porcelain, glass and other attractive and potentially fragile materials.

With these items, the child learns to do many everyday activities. He learns to prepare real food (not pretend

food) – using real knives to cut strawberries, real peelers to peel carrots, real porcelain plates, (not plastic)

to set the table. He carries little pitchers of water, and pours his friend a drink, into a real, open glass

not a sippy cup.

Inside View

The materials we use are largely “self-correcting”: they are designed

so that the child can recognize on his own, without the teacher, whether he has completed the activity

correctly. This is particularly true of the Practical Life activities: when he carries a pitcher full

of water, and does not coordinate his movements, the water will spill; when he pours rice from one container

into another, any grains that land on the table provide feedback to pour more carefully next time; when he

drops a real glass and it breaks, he learns about the need to better balance the little tray.

By locating the feedback within the materials, we free the child to learn directly from reality – to

recognize that the reason to do the work is not to get the approval of adults or other children,

but to succeed at a real task, objectively, through his independent effort, and by his own thinking

and judgment.

Results

Independence, Higher Attention Concentration and Executive Functions

A sense of order

Between the ages of 2 and 3, children actually crave order. Our structured environment meets that need – and by enabling the child to find an activity in its proper place and to return it there, we encourage and solidify this sense of orderliness, much to the child’s later benefit.

Concentration skills

It is in Practical Life that young children first learn to extend their attention span – by repeating activities they find interesting, over and over again, until they have mastered them.

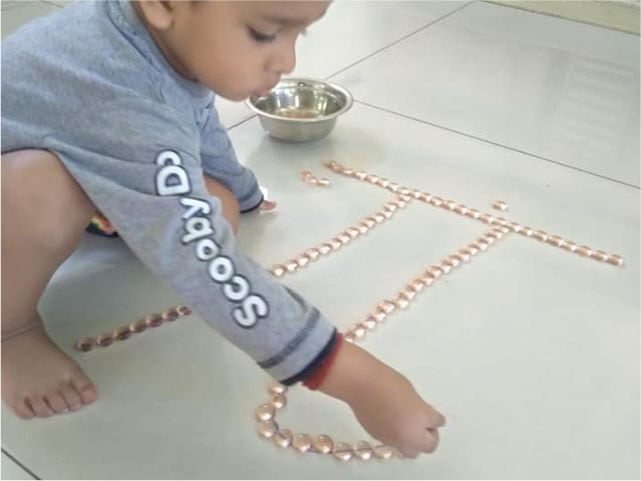

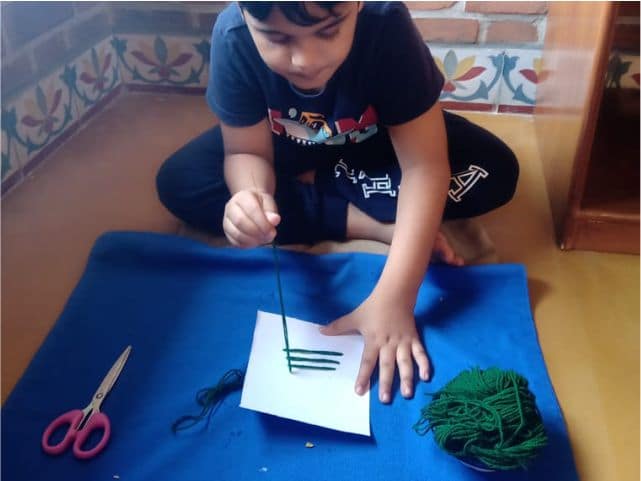

Fine Motor Skills

Picking up small beans with three fingers and stringing them, using tongs to transfer items from one bowl into another, using droppers to transfer water – all these activities help strengthen the hand and prepare it for the later tasks of holding a pencil and writing.

Independence – and a Broad Range of Mental and Physical Skills

The goal of Practical Life is two-fold: Obviously, the children learn to t

ake care of themselves, and delight in being able to perform grown-up tasks as well. They become

independent of adult help at an age where they are eager to do things for themselves.

The fundamental benefit of Practical Life, however, is even deeper. By practicing these

multi-step, everyday activities, our students learn a wide range of important life skills:

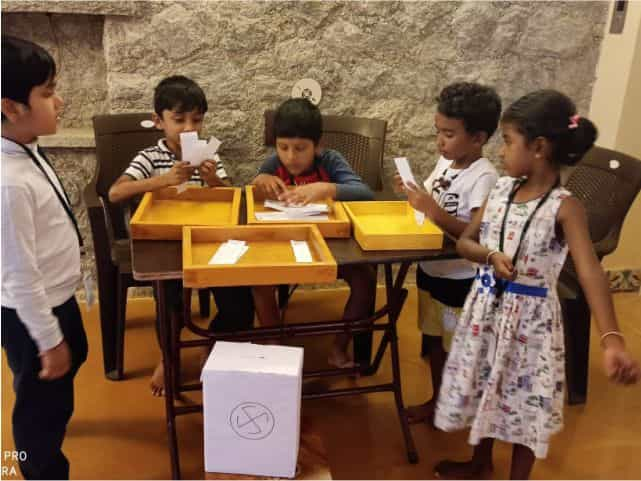

Executive functioning

Our 4-year-olds are able to plan, and then perform, processes with

10 or more steps and to do them in the correct sequence, with a high standard of care. They

also learn to exercise the mental discipline necessary to master their impulses.

For example, as each material exists only once in any given classroom, our students learn

to wait for their turn while someone else is using a material, and to do so gracefully,

without complaining or snatching the work from their peer.

Motor coordination

In conducting their daily activities — whether it is carrying a pitcher full of water, or balancing the materials on a tray as they walk around their peers’ little tables and mats, whether it is pouring water or drying a porcelain dish – our students learn to exercise and coordinate their large muscles. In taking action, they get immediate feedback: if they are not coordinated, the water will spill, the glass pitcher may fall and break, or the items may slide off the tray. This self-correcting nature of Practical Life activities allows the child to learn from direct feedback – and to see for himself how his skills grow as a result of his dedicated efforts.

Gross motor skills

In conducting their daily activities — whether it is carrying a pitcher full of water, or balancing the materials on a tray as they walk around their peers’ little tables and mats, whether it is pouring water or drying a porcelain dish – our students learn to exercise and coordinate their large muscles. In taking action, they get immediate feedback: if they are not coordinated, the water will spill, the glass pitcher may fall and break, or the items may slide off the tray. This self-correcting nature of Practical Life activities allows the child to learn from direct feedback – and to see for himself how his skills grow as a result of his dedicated efforts.

Social skills, including Grace and Courtesy

Throughout their time with us, but especially during Practical Life activities such as preparing, serving and sharing snacks, we coach our children to treat each other kindly and to respect each other’s personal space and work. We show them how to practice social graces such as saying “please” and “thank you”, and to ask for cooperation or help in a respectful manner, including not interrupting others’ conversations. Our students graduate able to conduct themselves with good manners, and to interact maturely and with poise, with peers and adults alike.

A sense of pride in being able to do real, adult activities

Our students learn that they can get better, that practice does lead to improvement over time. They experience the reward of task mastery – and see that they acquire it by applying themselves and practicing. The result is a profound, deeply engrained, pro-work attitude: they enjoy acting in the world, know the pride of a job well done, and feel the blossoming esteem of knowing they are of able body and able mind.

Get in Touch with Us

Our Headquarters are in Chennai and Puducherry

27-28, 2nd Cross

Moogambigai Nagar

Reddiarpalayam, Pondy - 605 010

Phone: +91 9994851951

Phone: +91 9361919996

Email: contact@vrukshamontessori.com

24-25, 12th Cross

Ranga Reddy Gardens

Neelankarai, Chennai - 600 041

Phone: +91 9994851951

Phone: +91 9361919996

Email: contact@vrukshamontessori.com